Fixed NPRIs

Characteristics

A fractional royalty interest

A fixed fraction of total production

The stand-alone right to a particular share of the proceeds from production

Not proportionately reduced based on the lease royalty rate

Constant, regardless of the amount of royalty contained in a subsequently negotiated oil and gas lease

Examples

A one-fourth royalty in all oil, gas and other minerals in and under and hereafter produced;

A free royalty of 1/32 of the oil and gas;

An undivided one-sixteenth royalty interest of any oil, gas or minerals that may hereafter be produced;

An undivided 1/24 of all the oil, gas and other minerals produced, saved, and made available for market;

1% royalty of all the oil and gas produced and saved;

Joe Smith grants Jane Doe an undivided 1/16 of the oil, gas & minerals produced and saved and made available for market.

Jane doe is now entitled to a fixed 1/16th royalty from production, irrespective of the lease royalty rate.

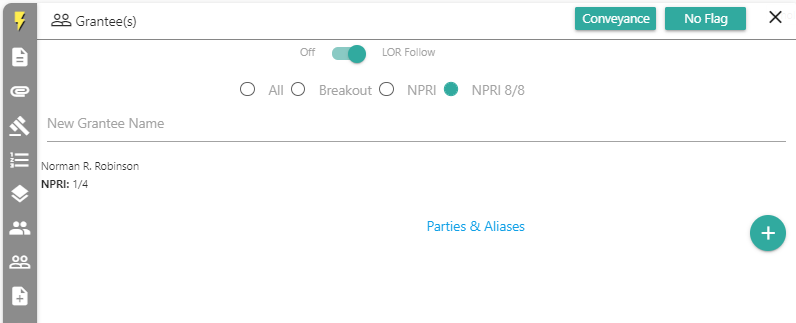

Tracts Entry

Select the “NPRI 8/8” button in the Quick-Entry tab to convey a fixed NPRI.

Here’s what “A one-fourth royalty in all oil, gas and other minerals in and under and hereafter produced” would look like on the digital notecard.

Floating NPRIs

Characteristics

A fraction of royalty interest (as a percentage of production)

Interest shares in a portion of the royalty and varies, or floats, with the lease royalty rate

The NPRI owner’s royalty is proportionately reduced according to the lease royalty rate

Examples

An undivided ½ interest in and to all of the royalties received from any oil & gas leases;

One-half of ⅛ of the oil, gas, and other mineral royalty that may be produced;

One-half of the usual one-eighth royalty that may be produced in the future;

1/16th of all oil royalty;

An undivided 2/3 of all royalties;

Joe Smith grants John Doe an undivided ½ interest in and to all of the royalties received from any oil & gas leases.

If Joe Smith signs a lease with a one-eighth lease royalty rate, John Doe is entitled to a 1/16th royalty from production.

If the above lease expires and Joe Smith later signs a lease with a 1/5th royalty rate, John Doe is entitled to a 1/10th royalty from production.

Tracts Entry

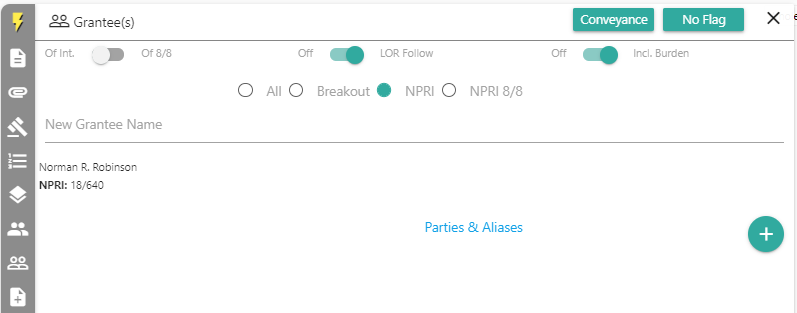

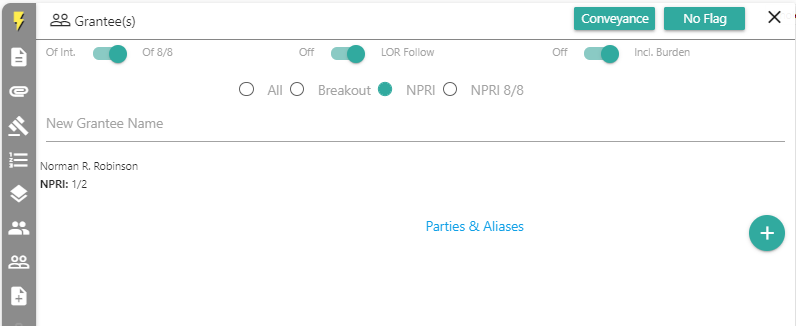

Select the “NPRI” (not “NPRI 8/8”) button in the Quick-Entry Tab to convey a floating NPRI in Tracts.

On the Grantee tab, be careful to distinguish as to whether the Grantor is conveying:

“Of Int.”: An undivided 18/640 of Grantor’s interest in and to all of the oil and gas royalty”

“Of 8/8”: An undivided 1/2 interest in and to all of the oil and gas royalty

Establishing/Defending Reasonable Interpretations

Particularly in Texas, courts have had a hard time deciding on language that establishes the “fixed” or “floating” nature of NPRIs.

The most common causes of controversy are:

- Multi-clause deeds–Deeds including a granting clause as well as a subject-to clause, and/or a future-lease clause;

- The use of a double-fraction and lack of clarity as to whether a referenced “one-eighth” relates to:

-

- The Customary One-Eighth Royalty–It was once commonly believed that the lease royalty reserved by a lessor always was and always would be one-eighth.

- Estate Misconception Theory–This theory is applied by a reviewer who believes an author was under the misconception that the leasing of minerals reduced a lessor’s mineral interest to one-eighth.

-

Landmen are certainly not tasked with rendering a legal opinion regarding ambiguity in NPRI reservations and conveyances.

However, Tracts does allow landmen to Flag any instrument that includes ambiguous language and to Flag a note that defends their interpretation. This allows reviewers to accept or revise those interpretations quickly.

Relevant Court Cases

Knowledge of the court cases linked below, and others, will help landmen establish and defend reasonable interpretations of fixed and floating NPRIs:

The Court determined that when the granting clause conflicted with other parts of the deed, the granting clause controlled because true intent should be found there. The Court overruled this case in Luckel v. White (Tex. App. 1991).

Luckel v. White (Tex. App. 1991)

The Court overruled Alford v. Krum and determined that the future lease clause was effective to convey a one-fourth interest in all royalties as to future leases (floating).

[“Granting” clause]

“I, Mary Etta Mayes,… [convey to] L.C. Luckel, Jr. an undivided one thirty-second (1/32nd) royalty interest in and to the following described property,…

[“Habendum” and “Warranty” clauses]

TO HAVE AND TO HOLD the above described 1/32nd royalty interest… unto the said L.C. Luckel, Jr. his heirs and assigns forever… to warrant and forever defend… the said 1/32nd royalty interest…”

[“Subject-to” clause]

“It is understood that said premises are now under lease originally executed to one Coe and that the grantee herein shall receive no part of the rentals as provided for under said lease, but shall receive one-fourth of any and all royalties paid under the terms of said lease.”

[“Future lease” clause]

“It is expressly understood and agreed that the grantor herein reserved [sic] the right upon expiration of the present term of the lease on said premises to make other and additional leases… and the grantee shall be bound by the terms of any such leases… [and] shall be entitled to one-fourth of any and all royalties reserved under said leases.”

[Final clause]

“It is understood and agreed that Mary Etta Mayes is the owner of one-half of the royalties to be paid under the terms of the present existing lease, the other one-half having been transferred by her to her children and by the execution of this instrument, Mary Etta Mayes conveyed one-half of the one-sixteenth (1/16th) royalty now reserved by her.”

The Court explained that the “proper way to harmonize the provisions of the Mayes-Luckel deed, consistent with our prior decisions under the four corners rule, is to hold that upon the termination of the Coe lease, Luckel owns an undivided one-fourth of the reserved royalty in all future leases. We, therefore, overrule Alford v. Krum.”

Hudspeth v. Berry (Tex. App. 2010)

The Court determined “because the 1943 deed does not contain conflicting fractions, and because the plain language of the deed is unambiguous, we hold that the reservation clause in the 1943 deed provides for a “fractional royalty” interest rather than a “fraction of royalty” interest.”

“There is, however, expressly reserved and excepted from this conveyance, for the benefit of J. H. Berry, his heirs or assigns, and [sic] undivided 1/40th royalty interest (being 1/5th of 1/8th) and for the benefit of R. C. Berry, his heirs or assigns, an undivided 1/40th royalty interest (being 1/5th of 1/8th) . . . . But the grantee herein, his heirs or assigns, may, and they are hereby expressly authorized to lease the said land at will for oil, gas and other mineral privileges without our consent or ratification but in any such lease or leases, there shall be reserved the usual 1/8th royalty of which 1/8th J. H. Berry shall be entitled to and receive 1/5th, and R. C. Berry shall be entitled to and receive 1/5th.”

Sundance Minerals, L.P. v. Moore (Tex. App. 2011)

The Court determined that a 1/2 floating NPRI was reserved when the grantor reserved:

“one-half of the usual one-eighth royalty.”

The Court explained that the reference to the usual 1/8th royalty was “merely an example showing the type of interest they intended to reserve, not a further limitation.”

Coghill v. Griffith (Tex. App. 2012)

The court determined that if a deed acknowledges the possibility of future leasing, then the parties likely intended a floating royalty.

“…an undivided 1/8th interest in and to all of the oil and gas royalty… as well as an undivided 1/8th of the usual 1/8th royalties provided for in any future oil, gas and/or mineral lease…”

Moore v. Noble Energy, Inc. (Tex. App. 2012)

The Court determined that the following reservation was for a fixed 1/16th NPRI, being 1/2 of 1/8th:

“a one-half NPRI (1/2 of 1/8th of production)”

The Court explained that this interest was tied to production and that it was unreasonable to conclude the grantor meant to reserve a fixed 1/2 NPRI of all production.

Wynne/Jackson Dev. L.P. v. Pac Capital Holdings, LTD (Tex. App. 2013)

The Court determined that the deeds in this case reserved what is known as a fractional royalty (fixed).

“NPRI of 1/2 of the usual 1/8th royalty in and to all oil, gas and other minerals produced, saved and sold from the property.”

The Court expressed that the distinction between Sundance Minerals case and this one was that the deeds in this case did not purport to reserve an undivided interest in the entire mineral estate, and further that the deeds in this case, unlike the deed in Sundance Minerals, clearly reserve the rights of the grantor as they relate to bonus and delay rentals. Finally, the Court expressed that lumping the reservations together as a single reservation “would blur the distinction between different components of the mineral estate when the deeds clearly sought to maintain that distinction.”

Graham v. Prochaska (Tex. App. 2014)

The Court determined that a 1950 deed was constructed under the misconception that lease royalty rates would always be 1/8th. Therefore, the Court determined that the following language resulted in a floating NPRI reservation:

“one half (1/2) of the one-eighth (1/8th) royalty to be provided in any and all leases for oil, gas, and other minerals now upon or hereafter given.”

The court further expressed that this reasoning should not be used unless the language in the deed objectively establishes that the author was under the above misconception

Hysaw v. Dawkins (Tex. App. 2016)

The Court determined that a double-fraction reflected a floating royalty, in this case.

Grants in this case were from a Will (probated in 1949) with many inconsistencies.

Hysaw is seen as a seminal case, making the statement that the language within conveyances cannot always be relied upon to resolve ambiguities as to whether or not an NPRI is fixed or floating and that Courts must take a holistic approach to interpret parties’ intent within an instrument by harmonizing all its language.

The Court determined that a deed with the following conveying language conveyed a floating NPRI:

“all of their right, title, and interest in and to the Seven-eighths (7/8 SHARE) royalty, of all of the oil and of all the gas produced and saved from hereinafter described lands.”

The Court explained that “the language in the intent clause does not contradict the conveying language but explains the royalty interest was to be computed.” The Court further specified that the intent language stated “of the total royalty” and not “of the total production.”

“…so that each assignee receives an undivided one-eighth share of the total royalty.”

U.S. Shale Energy II, LLC v. Laborde Props., L.P. (Tex. 2018)

A 1951 deed reserved “An undivided ½ interest in and to the [royalty of the oil, gas and other minerals] in and under or that may be produced or mined from …the premises, the same being equal to 1/16th of the production.”

The question for the Court to decide was whether the second clause rendered this a fixed royalty, or if it simply modified the first clause, which clearly represented a floating royalty.

The lands were not leased at the time of the deed, so the Court expressed:

the deed likely referred to future leasing;

the author of the deed likely assumed future lease royalties would be 1/8th.

Further, the Court discussed that the language offset by the comma is a nonrestrictive dependent clause and that such a clause further describes or informs the central meaning of a sentence, rather than changing it.

Therefore, though it’s worth noting that a dissenting opinion criticized the conclusion that the first clause reserved a floating royalty, the Court determined that this was a floating royalty reservation.